Until the mid-1980s, there were only 320 confirmed sightings of whale sharks worldwide.

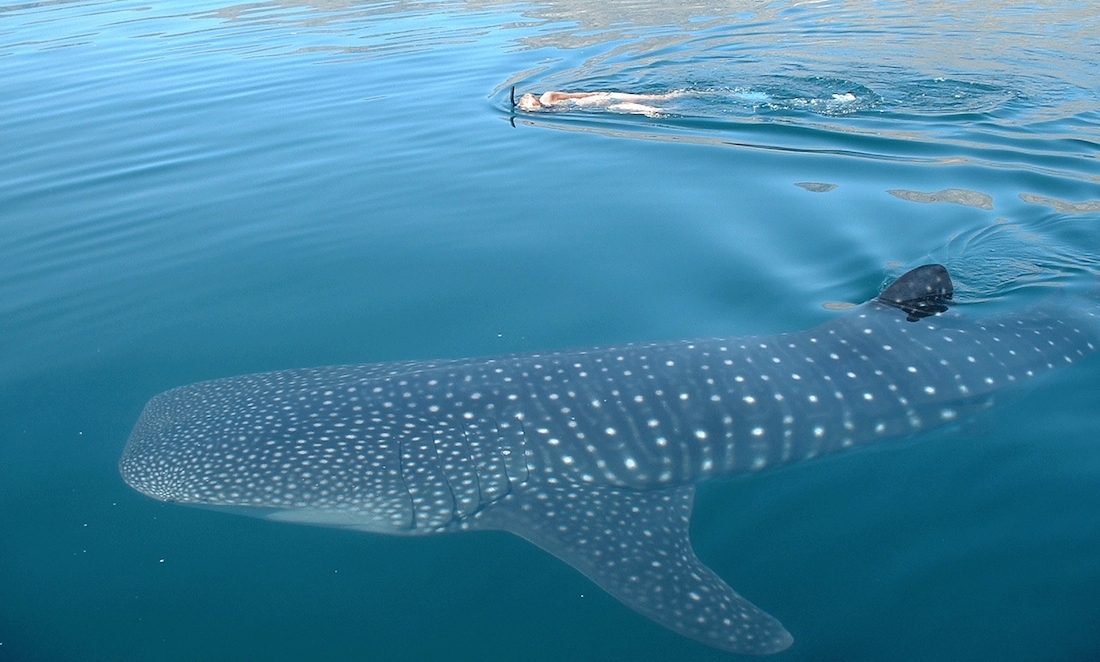

Marine biologists still don’t know where the gentle giants mate and give birth.

But a project to discover where Ningaloo’s whale sharks go when they’re not hanging out at the World Heritage-listed reef is starting to unearth some of the secrets of these elusive creatures.

ALBANY TO ASHMORE REEF

Whale shark expert and ECOCEAN founder Dr Brad Norman says the most of the sharks at Ningaloo are immature males.

These teenage boys are likely drawn by large amounts of food available at the reef.

Brad says there’s a strong possibility that when whale sharks mature they swim offshore “into the deep blue” to find a mate.

“We’re really keen to ramp up the research that we’re doing with some tracking work [in 2017] and beyond, to concentrate on finding the mature individuals at Ningaloo,” he says.

“There’s still a few big ones that are of a sexually active age, so they’re the ones we want to target… to see where they go.”

It could be that for the whole WA coast is a whale shark playground.

One recent study used satellite tracking, a photo library and interviews with people in 14 towns along the WA coast.

It recorded whale shark sightings from Albany to Ashmore Reef, north of Broome.

LEAVING HOME

What worries Brad is what happens to the whale sharks when they leave protected Australian waters.

In 2000, he authored a report that saw the conservation status of whale sharks change from unknown to ‘vulnerable to extinction’.

A 2016 update saw the animals’ status further downgraded to ‘endangered’.

While Ningaloo Reef is bucking the global trend, there are places offshore where whale sharks are vulnerable, Brad says.

“That’s one of the reasons we do want to do further research as well—to establish whether our whale sharks at Ningaloo are moving to areas where they may be at greater risk.”

ONE OF AUSTRALIA’S LONGEST-RUNNING CITIZEN SCIENCE PROJECTS

Long before anyone had heard of citizen science—the term was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2014—Brad was a young marine biologist taking photos of whale sharks with a slide camera.

“Whale sharks are covered in spots so there was a likelihood that the markings on their skin was like a fingerprint,” he says.

Brad had an idea that tourists’ photos could be used to identify whale sharks, and in 1995 the whale shark photo library was born.

“I thought, ‘I’m only in one spot on one day, but using this technique, using simple photo ID, members of the public could participate’,” he says.

“‘There’s thousands of people going swimming with whale sharks each year’.

“Put a camera in the hands of each of those and they can become my research assistant for the day’.”

“We needed to make it simple and we needed to make it something that anyone could do.”

Today, the Whale Shark Photo-identification Library pioneered by ECOCEAN is the largest whale shark monitoring project in the world.

It contains more than 50 000 photos from around the globe.

GET INVOLVED

Despite whale sharks’ iconic status, ECOCEAN doesn’t receive government funding or big grants.

The organisation relies on heavily on volunteers and private donors to continue the research.

They also have good relationships with tour boat operators and partnerships with schools.

“We’re definitely looking to see where we can get the funds to make sure we keep this project going from strength to strength,” Brad says.

To contribute a photo to the whale shark library, or support the research, visit whaleshark.org.au.